MIST

Magnetosphere, Ionosphere and Solar-Terrestrial

Nuggets of MIST science, summarising recent papers from the UK MIST community in a bitesize format.

If you would like to submit a nugget, please fill in the following form: https://forms.gle/Pn3mL73kHLn4VEZ66 and we will arrange a slot for you in the schedule. Nuggets should be 100–300 words long and include a figure/animation. Please get in touch!

If you have any issues with the form, please contact This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Jupiter’s X-Ray and UV Dark Polar Region

By Daisy May and Ben Sipos (St Gilgen’s School)

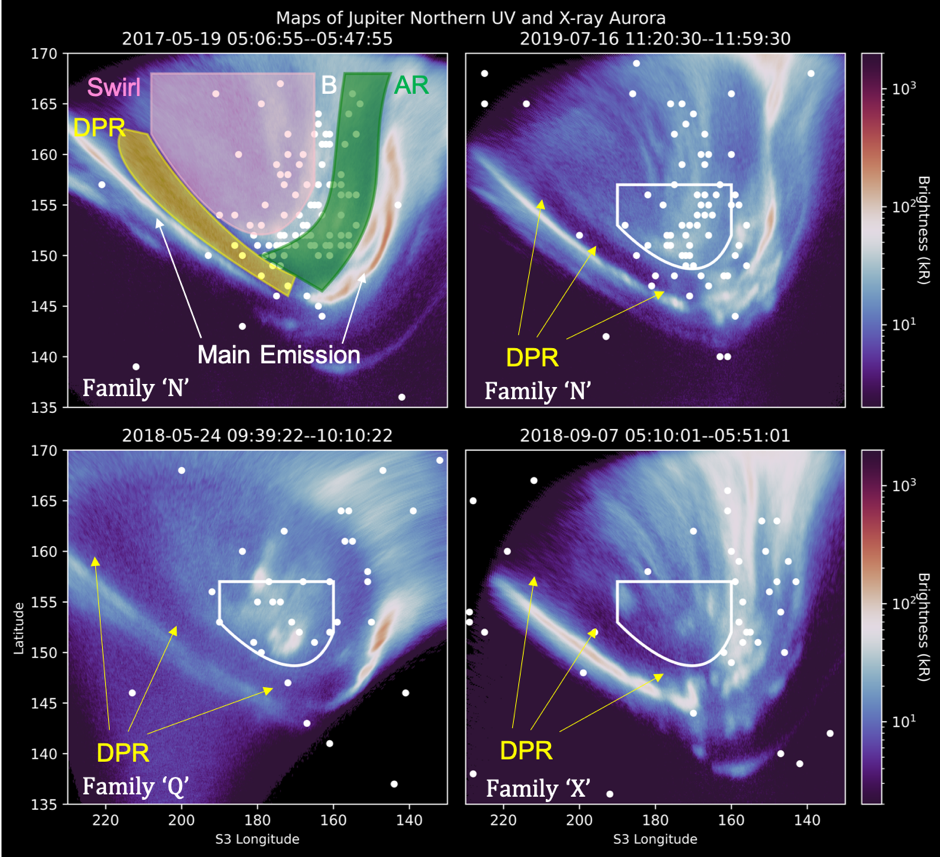

Jupiter produces powerful ultraviolet (UV) and X-ray aurorae at the planet’s poles. The emissions take on a variety of dynamic structures, particularly in the swirl and active regions (Figure 1). However, the dark polar region (DPR) consistently demonstrates a lack of auroral emissions. 14 simultaneous Chandra X-ray Observatory and Hubble Space Telescope observations of Jupiter’s Northern aurorae (between 2016 and 2019) revealed that no statistically significant X-ray signature is detectable within the DPR.

There were two potential non-DPR sources that might have contributed DPR photons, that needed to be considered. The first source was scattered solar photons. By shifting a region the same shape and size as the observed DPR across non-auroral longitudes of the planet, and scaling the photon counts to the duration of the HST observation, we determined the expected number of scattered photons in the DPR for each observation (0.3 to 1.4 counts depending on the DPR size, distance to Jupiter, and solar activity).

The second source was emissions perceived to have come from within the DPR due to the spatial uncertainty of the X-ray Observatory. To determine the count of such photons, we simulated where photons that were produced from the active and swirl regions would have been detected when passed through the spatial uncertainties applied by the X-ray observatory. After 100,000 simulations for each observation, we determined the count of such falsely detected photons, and found that there is no statistically significant X-ray detection from the DPR for these 14 observations.

The lack of x-rays implies low levels of precipitation by solar wind and energetic magnetospheric ions in the DPR. Therefore, the observations are consistent with the DPR being associated with either: Jupiter’s open field line region and/or the DPR containing different potential drops or an absence of the strong downward currents and/or wave-particle interactions present across the rest of the polar aurorae.

This research project was undertaken with the Orbyts programme which partners scientists with schools to support school student involvement in research and to improve inclusivity in science. This nugget was written by two school students who produced a significant proportion of the work in the associated paper.

Figure 1: Overlaid simultaneous UV (blue-white-red color map) and X-ray photon (white dots) longitude-latitude maps of Jupiter's North Pole, from the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) and Chandra X-ray Observatory High Resolution Camera (CXO-HRC). Dates and times of the observations (UT) are at the top of each panel. Only UV and X-ray emissions produced during this time window are shown. Jupiter’s main emission is labelled by white arrows, the dark polar region (DPR) is shown in yellow, the Swirl region is shown in pink and the Active Regions (sometimes split into a noon and dusk active region) are shown in Green. The boundary between the active region and swirl region (here labelled with a white “B”) sometimes includes an arc of UV and X-ray emission, as is the case for the two different observations shown in the top two panels here. The other panels highlight three different UV aurora families, as indicated by the white label in the lower left corner of each (Grodent et al. 2018). The white shape overlaid onto each map is consistent across each, and highlights the changing spatial distribution of X-rays for each. For each panel, the location and extent of the DPR are indicated with yellow arrows, showcasing its changing extent from observation-to-observation.

References: Grodent, D., Bonfond, B., Yao, Z., Gérard, J.-C., Radioti, A., Dumont, M., et al. (2018). Jupiter’s aurora observed with HST during Juno orbits 3 to 7. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, 123(5), 3299– 3319.

Associated Paper: Dunn, W.R., Weigt, D.M., Grodent, D., Yao, Z.H., May, D., Feigelman, K., Sipos, B., Fleming, D., McEntee, S., Bonfond, B. and Gladstone, G.R., 2022. Jupiter’s X‐ray and UV Dark Polar Region. Geophysical Research Letters, p.e2021GL097390.

Data Assimilation and the Solar Wind

By Harriet Turner (University of Reading)

Data assimilation (DA) combines model output and observations to form an optimal estimation of reality. It has led to large improvements in terrestrial weather prediction, reducing the “butterfly effect”, by which small errors in the initial conditions can grow non-linearly and lead to large errors in the subsequent forecast.

DA has been used in three main areas for space weather forecasting: the ionosphere, the photosphere, and, more recently, the solar wind. The first attempts at using DA for solar wind forecasting has shown promise, with a reduction in forecast error (Lang, 2021).

I have been using the Burger Radius Variational Data Assimilation (BRaVDA) scheme (Lang, 2019). This uses output from a coronal model with a computationally efficient solar wind model (HUX; Riley and Lionello, 2011) to map information from in-situ observations at Earth’s orbital radius (215 solar radii), back to the HUX inner boundary at 30 solar radii. The inner boundary conditions are then updated, given the information from the in-situ observations. This update is then run forward in time, again using HUX, to produce a reconstruction of the solar wind. This can then be used for forecasting.

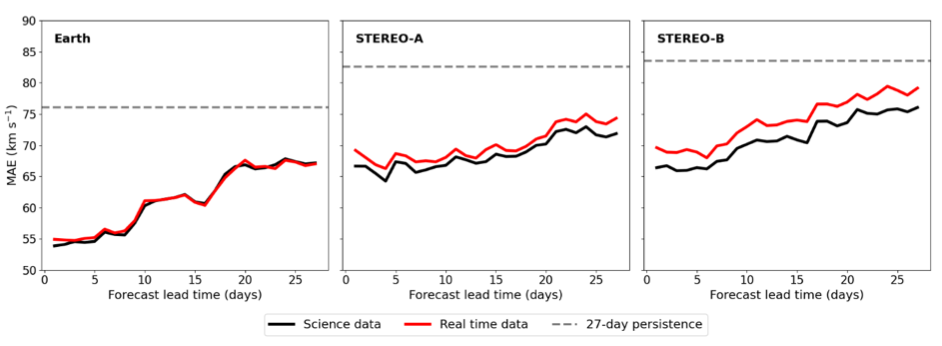

We have three sources of observations: STEREO-A, STEREO-B, and the OMNI dataset for near-Earth space. For the purposes of my work, I am using a simple corotation to produce a forecast. We can compare this forecast against observations from the three sources to assess its performance. Recently, I have been looking at testing the performance of BRaVDA with real time data. Previous experiments have used cleaned-up, science-level data, but real time data would need to be used for an operational DA scheme. Initial results show that using the real time data does not worsen the forecasts significantly and is still an improvement from a 27-day persistence forecast, as shown in Figure 1, which is promising for future implementation of solar wind DA.

Figure 1: Mean absolute error (MAE) of solar wind forecasts as a function of forecast lead time, for the case where OMNI, STEREO-A and STEREO-B observations are assimilated together. The black line shows the forecast where the science-level data was used and the red line when real time data was used. The dashed grey line shows the average 27-day persistence MAE for the specific spacecraft. The left-hand panel shows the forecast at Earth, the middle panel shows the forecast at STEREO-A and the right-hand panel shows the forecast at STEREO-B. This covers the period from 01/04/2012 to 01/10/2013.

References:

Lang, M., & Owens, M. J. (2019). A Variational Approach to Data Assimilation in the Solar Wind. Space Weather, 17(1), 59 – 83. Doi: 10.1029/2018SW001857.

Lang, M., Witherington, J., Owens, M. J., & Turner, H. (2021). Improving solar wind forecasting using data assimilation. Space Weather, 1 – 23.

Riley, P., & Lionello, R. (2011). Mapping Solar Wind Streams from the Sun to 1 AU: A Comparison of Techniques. Solar Physics, 270(2), 575 – 592. Doi: 10.1007/s11207-001-9766-x.

Assessing the Impact of Weak and Moderate Geomagnetic Storms on UK Power Station Transformers

By Zoë Lewis (Imperial College London)

Geomagnetically induced currents (GICs) are known to cause damage to power station transformers, as they can flow through the grounded neutral and generate extra magnetic flux, causing localised heating. This heating can break down the insulation and cooling oil that surrounds the core, so can be measured through small changes in the concentrations of dissolved gases within the oil.

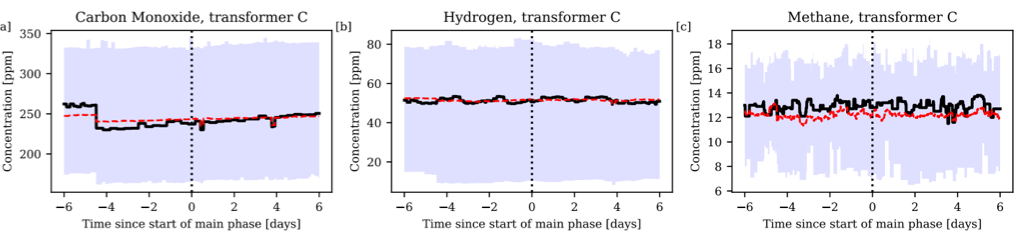

In this work, we analysed dissolved gas data from 13 UK based transformers during geomagnetic storms from 2010-2015. We used a list of storms outlined in [1] and looked for an increase in the levels of carbon monoxide, hydrogen, and methane at the onset of the storm, as well as any correlation between the rate of gas increase and the SYM-H index. We also used the Low Energy Degradation Triangle (LEDT) method [2] as a measure of degradation.

Figure 1 shows the results of a superposed epoch analysis (SEA) for carbon monoxide, methane and hydrogen in one transformer. The epochs are centred on the start of the main phase of each storm, as defined in [1]. There is no systematic increase in the gas concentrations at the storm onset or in the following days. The interquartile range (shaded blue) is also very large owing to the highly variable data.

We conclude that during this period, the transformers studied were unaffected by space weather events. However, it is noted that 2010-2015 lies within a relatively quiet solar cycle, and there were no storms in this period that would be considered large on the scale of the past few decades. Therefore, in future work it would be desirable to expand this study to look at a more geomagnetically active period.

[1] Walach, M. T., & Grocott, A. (2019). SuperDARN Observations During Geomagnetic Storms, Geomagnetically Active Times, and Enhanced Solar Wind Driving. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, 124 (7), 5828–5847. doi: 10.1029/2019JA026816

[2] Moodley, N., & Gaunt, C. T. (2017). Low Energy Degradation Triangle for power transformer health assessment. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation, 24 (1), 639–646. doi: 10.1109/TDEI.2016.006042

Please see paper for full details: , , , & (2022). Assessing the impact of weak and moderate geomagnetic storms on UK power station transformers. Space Weather, 20, e2021SW003021. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021SW003021

Transpolar Arcs: Seasonal Dependence Identified by an Automated Detection Algorithm

By Gemma E Bower (University of Leicester)

Transpolar arcs (TPAs) are primarily a northward IMF auroral phenomena. They consist of an arc of auroral emission poleward of the main auroral oval. Their presence suggests that the magnetosphere has a complicated magnetic topology. Currently, TPA formation and evolution have no single explanation that is unanimously agreed upon.

In order to further study the occurrence of TPAs we have developed an automated detection algorithm to determine the occurrence of TPAs in UV images captured by the Defense Meteorological Satellite Program/ Special Sensor Ultraviolet Spectrographic Imager (DMSP/SSUSI) from spacecraft F16, F17, and F18. The detection algorithm identified TPAs as a peak in the average radiance intensity poleward of 12.5° colatitude, in two or more of the wavelengths/bands sensed by SSUSI.

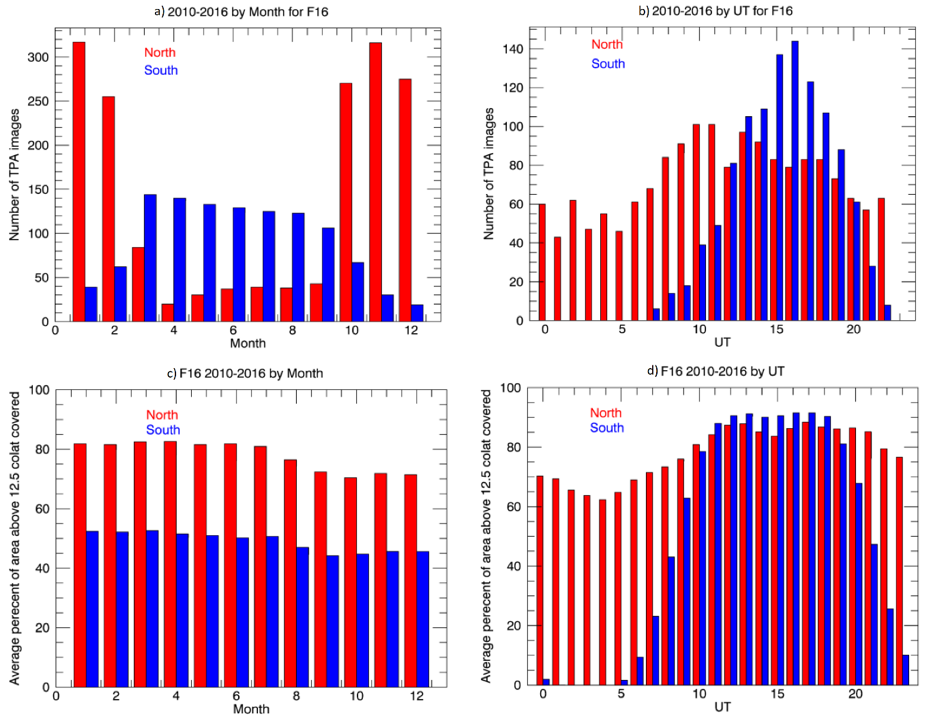

Over 5,000 SSUSI images containing TPAs were identified by the detection algorithm between the years 2010 to 2016. Figure 1a and b shows the seasonal and UT distribution for the F16 TPA images respectively. The occurrence of these TPA images shows a seasonal dependence, with more arcs being visible in the winter hemisphere. There is also an apparent dependence on time-of-day, especially in the southern hemisphere where no TPAs are seen between 23 and 06 UT.

We investigated the effect that the orbital plane of DMSP has on the area of the detection window scanned, as a possible explanation of the dependences in the results of the detection algorithm. Figure 1c and 1d show the results for F16 for seasonal and UT distribution respectively. It can be seen that the orbital plane of DMSP leads to a preferential observation of the northern hemisphere, and the detection algorithm missing TPAs in the southern hemisphere around 01–06 UT. Hence, we conclude that there is no dependence of TPA occurrence on UT. No seasonal bias in the observations is found, indicating that the seasonal dependence of the TPA occurrence is real. We discuss the ramifications of these findings in terms of proposed TPA generation mechanisms.

Figure 1: (a-b) Number of transpolar arc (TPA) images identified by F16 between 2010 and 2016. (c-d) Average percent of the detection window poleward of 12.5° colatitude scanned by F16 between 2010 and 2016. (a and c) By month. (b and d) By UT. The northern hemisphere is red and the southern hemisphere is blue

Please see paper for full details: Bower, G. E., Milan, S. E., Paxton, L. J., & Imber, S. M. (2022). Transpolar arcs: Seasonal dependence identified by an automated detection algorithm. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, 127, e2021JA029743. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021JA029743

Variation of Geomagnetic Index Empirical Distribution and Burst Statistics Across Successive Solar Cycles

By Aisling Bergin (University of Warwick)

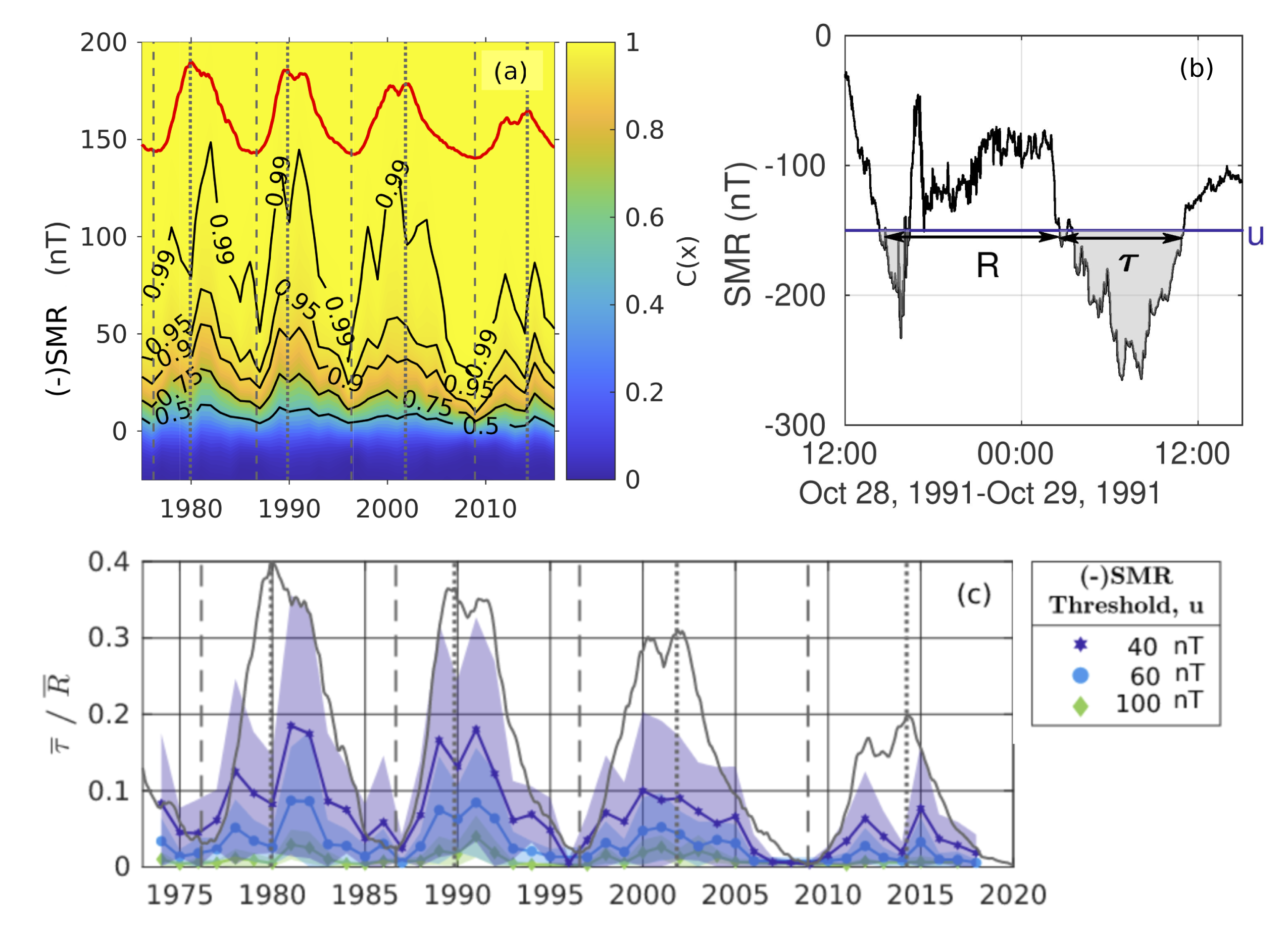

Geomagnetic indices, based on magnetic field observations at the Earth's surface, provide almost continuous monitoring of Earth’s magnetospheric and ionospheric activity. We analyze two geomagnetic index time series, AE and SMR, which track activity in the auroral region and around the Earth's equator, respectively. We show here that quantiles of the index distributions track solar cycle variation over solar cycles 21–24. The question is then how the likelihood of events varies with solar cycle activity.

In this paper, events are defined as bursts or excursions above a threshold which is either (i) a fixed value or (ii) a quantile of the distribution of the observed index values. We study the solar cycle dependence of the distributions of the burst return periods, R, and the burst durations, τ. A result from the theory of level crossings (LC) [1] constrains how , the ratio of the mean burst duration to return period, depends on the underlying empirical distribution of the observed quantity.

Our main results are as follows:

- At fixed value burst thresholds, is peaked in the declining phase for AE annual samples and follows the sunspot number double peak for SMR.

- Bursts are identified in samples at three distinct phases of the solar cycle. At fixed quantile thresholds the distributions of τ and R fall on single empirical curves for each of (i) the AE index at solar minimum, maximum, and declining phase and (ii) the SMR index at solar maximum. This goes beyond the constraint on average from LC theory.

- The tail of the empirical cumulative distribution functions of the observed values of the AE and SMR indices collapse onto common functional forms specific to each index and cycle phase when normalized to the first two moments of their exceedance distributions.

Taken together, these results may combine to offer important constraints in the quantification of overall space weather activity levels.

Please see the paper for full details: Bergin, A., Chapman, S. C., Moloney, N. R., & Watkins, N. W. (2022). Variation of geomagnetic index empirical distribution and burst statistics across successive solar cycles. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, 127, e2021JA029986. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021JA029986

[1] Lawrance, A., & Kottegoda, N. (1977). Stochastic modelling of riverflow time series. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A, 140(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.2307/2344516