MIST

Magnetosphere, Ionosphere and Solar-Terrestrial

Nuggets of MIST science, summarising recent papers from the UK MIST community in a bitesize format.

If you would like to submit a nugget, please fill in the following form: https://forms.gle/Pn3mL73kHLn4VEZ66 and we will arrange a slot for you in the schedule. Nuggets should be 100–300 words long and include a figure/animation. Please get in touch!

If you have any issues with the form, please contact This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Quantifying the number of false positive substorms identified in the SuperMAG SML index arising from enhancements in magnetospheric convection

By Christian Lao (MSSL, University College London)

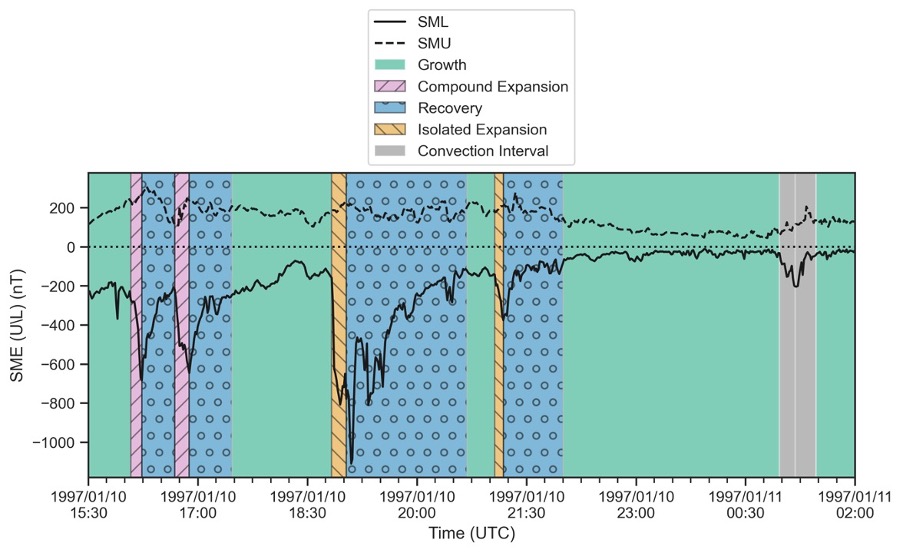

Substorms can be identified from negative bays in the SML index, which traces the minimum northward ground magnetic deflection at auroral latitudes, produced by enhancements of the westward electrojet. For substorms, negative bays are caused by the closure of the Substorm Current Wedge through the ionosphere, typically localized to the nightside and centred around 23-00 magnetic local time (MLT). In this case, the equivalent current pattern that causes the magnetic deflections is given the name Disturbance Polar (DP) 1. However, negative bays may also form when the westward electrojet is enhanced by increased convection, driving Pedersen and Hall currents in the auroral zone. Convection enhancements also strengthen the eastward electrojet, monitored by SMU index. In this case, the equivalent current pattern that produces the magnetic deflections is called DP2.

In this study, we investigated the contributions of the magnetic perturbations from the DP1 and DP2 current patterns to substorm-like magnetic bays identified in SML using the SOPHIE technique of Forsyth et al. (2015), https://doi.org/10.1002/2015ja021343. SOPHIE attempts to distinguish between the DP1 and DP2 enhancements, whereas other SML-based substorm identification methods don’t (e.g. Newell & Gjerloev, 2011; Ohtani+, 2020; etc). However, despite this, we find evidence that between 1997 and 2019 up to 59% of the 30,329 events originally identified by SOPHIE as substorms come from enhancements of DP2, which are unrelated to substorm phenomena, on top of the 2,627 convection enhancement events already identified. We highlight that any “substorm” list is, in fact, a list of magnetic enhancements, auroral enhancements, etc., which may or may not correspond to substorm activity and should be treated that way.

See publication for details:

, , , & (2025). Separating DP1 and DP2 current pattern contributions to substorm-like intensifications in SML. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, 130, e2024JA033592. https://doi.org/10.1029/2024JA033592

Estimating Electron Temperature and Density Using Van Allen Probe Data: Typical Behavior of Energetic Electrons in the Inner Magnetosphere

By Dovile Rasinskaite (Northumbria University)

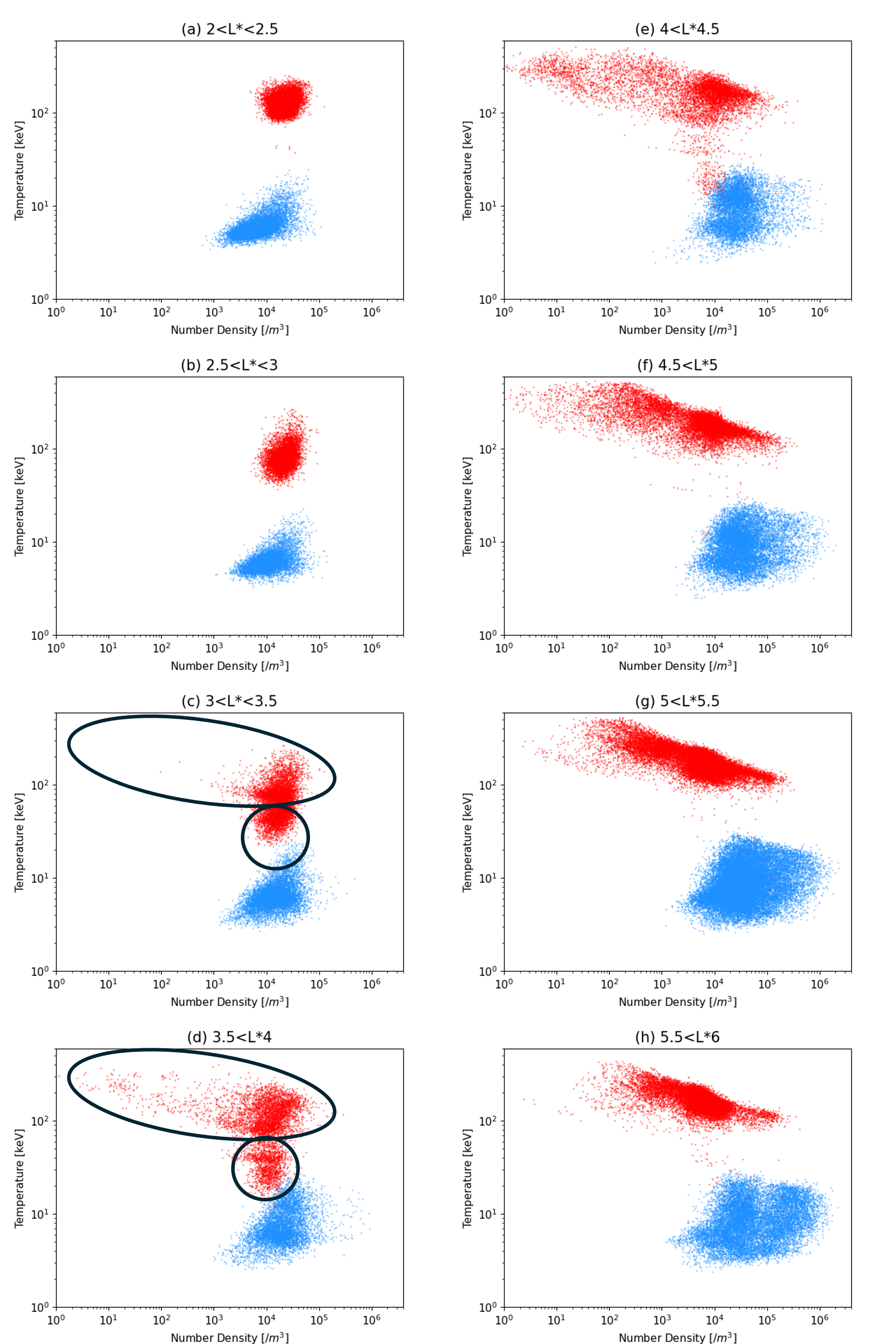

The Earth’s inner magnetosphere contains multiple electron populations influenced by different factors. The cold electrons of the plasmasphere, warm plasma that contributes to the ring current, and the relativistic plasma of the radiation belts often seem to behave independently. Using omni-directional flux and energy measurements from the HOPE and MagEIS instruments aboard the Van Allen Probes, we provide a detailed density and temperature description of the inner magnetosphere, offering a comprehensive statistical analysis of the entire Van Allen Probe era. While number density and temperature data at geosynchronous orbit are available, this study focuses on the warm plasma in the inner magnetosphere (2<L*<6). Values of density and temperature are extracted by fitting energy and phase space density to obtain the distribution function. The fitted distributions are related to the zeroth and second moments to estimate the number density and temperature. Analysis has indicated that a two Maxwellian fit is sufficient over a wide range of L* and that there are two independent plasma populations. The more energetic population has a median number density of approximately 1.2 * 104 m-3 and a temperature of around 130 keV, with a temperature peak observed between L* = 4 and L* = 4.5. This population is relatively uniform in MLT. In contrast, the less energetic warm electron population has a median number density of about 2.5*104 m-3 and a temperature of 7.4 keV. Strong statistical trends in density and temperature across both L* and MLT are presented, along with potential sources driving these variations.

See publication for details:

, , , , , , et al. (2025). Estimating electron temperature and density using Van Allen probe data: Typical behavior of energetic electrons in the inner magnetosphere. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, 130, e2024JA033443. https://doi.org/10.1029/2024JA033443

Dynamics of TEC High Density Regions Seen in JPL GIMs: Variations With Latitude, Season and Geomagnetic Activity

By Martin Cafolla (University of Warwick)

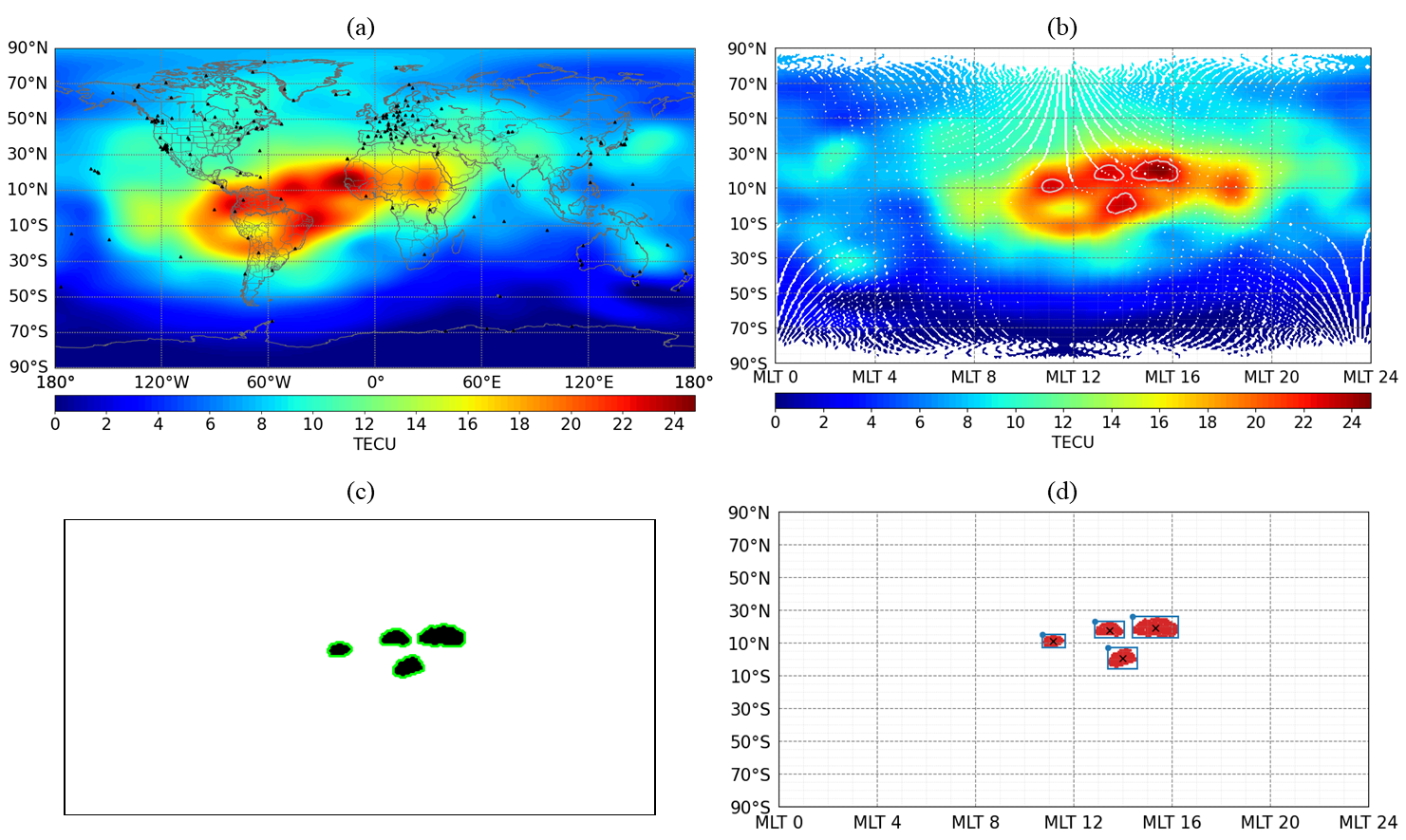

The ionosphere is a portion of the upper atmosphere of the Earth consisting of free electrons and ions as a result of exposure to solar radiation. The variability of intensity of this radiation, as well as the differing levels of geomagnetic activity, results in fluctuations in electron number density across the ionosphere, characterised by the Total Electron Content (TEC). We define High Density Regions (HDRs) of TEC, that is regions of enhanced line-integrated electron number density, as the top 1% of TEC measurements from Global Ionospheric Maps (GIMs). We then construct an algorithm that isolates, detects and tracks these regions for 20 years of TEC data in sun-centered geomagnetic coordinates. This produces a contiguous set of uniquely labelled space-time TEC HDRs. We conduct a statistical study to determine reproducible trends in HDR formation location, trajectories and durations for different levels of geomagnetic activity at continental and sub-continental (small) scales.

We find that HDR formation is primarily driven by the sub-solar point, spanning the afternoon ionosphere, and in general occurs around four magnetic latitude clusters. Small HDRs typically move along lines of constant magnetic latitude in the direction of Earth rotation, while continental scale HDRs have much more complex paths. The statistical nature of our results provides a probabilistic prediction on future HDR behaviour, offering an ensemble constraint on enhancements seen in ionospheric models.

Example TEC map for 2009-07-23 at 16:30:00 UTC. Panel (a) plots the geographic TEC map. Each 1 degree by 1 degree grid point plots the Vertical TEC at that longitude/latitude. Black triangles show the locations of ground stations. Panel (b) plots the geomagnetic TEC map with grey contours at the top 1% value of TEC in the map, defining the High Density Regions (HDRs). Panel (c) isolates these HDRs and plots them in black, with green contours drawn around each black region to demonstrate the algorithm’s contour detection. Panel (d) plots the isolated HDRs in SM coordinates with bounding rectangles in blue and centroids marked in black, obtained by the detection/tracking algorithm.

See publication for details:

Cafolla, M. A., Chapman, S. C., Watkins, N. W., Meng, X., & Verkhoglyadova, O. P. (2025). Dynamics of TEC high density regions seen in JPL GIMs: Variations with latitude, season and geomagnetic activity. Space Weather, 23, e2024SW004307. DOI: 10.1029/2024SW004307

Discovery of H3+ and infrared aurora at Neptune with JWST

By Henrik Melin (Northumbria University)

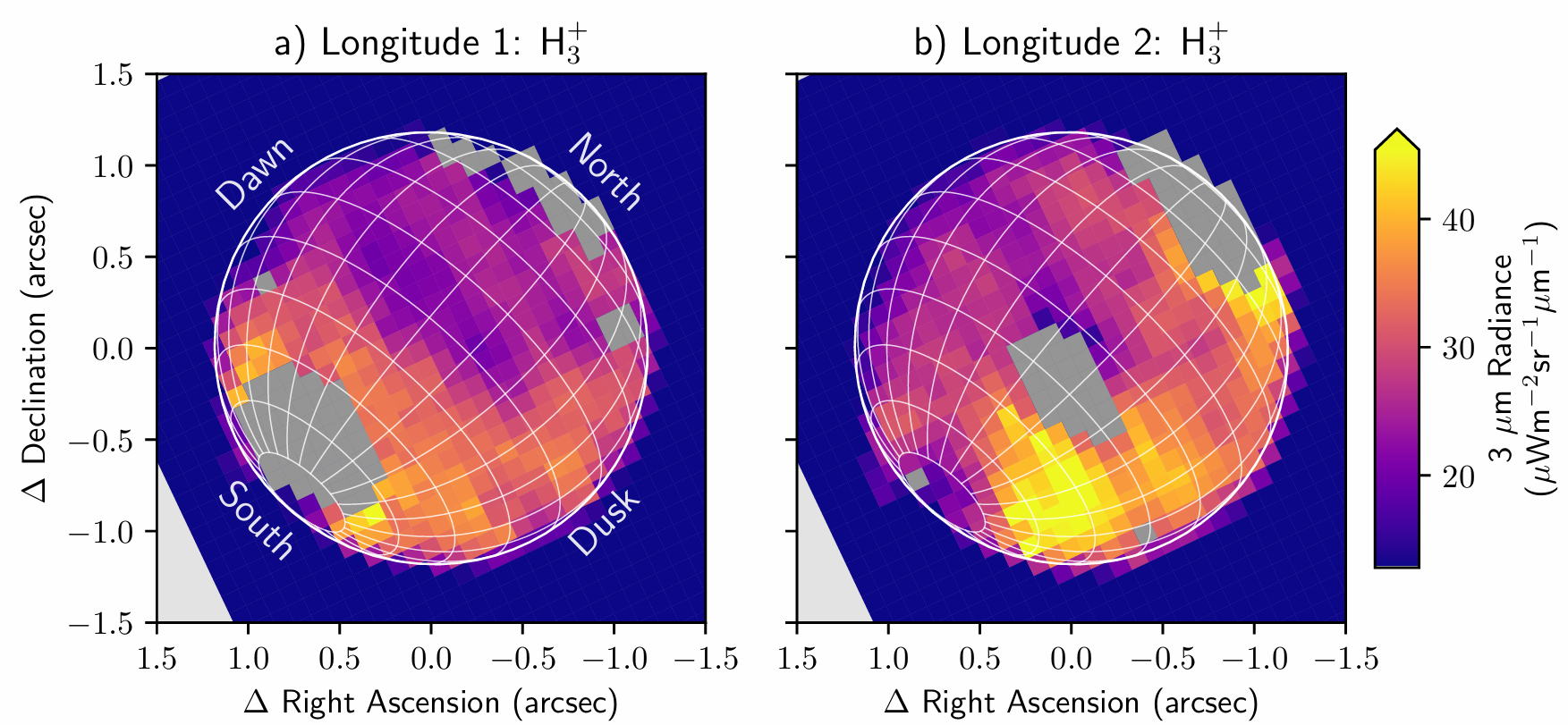

The molecular ion H3+ is a significant component of the ionospheres of the giant planets. By observing the near-infrared emission from this ion we can remotely diagnose the physical conditions of this region. This layer of the atmosphere is an importance conduit for energy transfer between the space environment, magnetic field, and the atmosphere below, and it is in this region that magnetospheric auroral currents deposit energetic electrons that form enhanced temperatures and densities of H3+.

H3+ was discovered at Jupiter, Saturn, and Uranus over 30 years ago and a great number of studies have been able to characterise the processes that occur in the ionospheres of these planets. However, despite many attempts using telescopes on the ground, H3+ has never been observed from Neptune, in spite of models predicting it should be detectable, based on data from the 1989 Voyager 2 encounter.

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is the most powerful telescope ever put into space, designed to observe the first galaxies formed in the early Universe. We can leverage this extraordinary sensitivity to explore our own cosmic backyard, by pointing the telescope at the giant planets. The first JWST observations of Neptune were taken in June 2023, and we were able to detect H3+ for the first time (yay!), as well as localised H3+ emissions about the magnetic pole. In other words, we were able to detect the ionosphere and aurora of Neptune for the first time, exactly 100 years after it was discovered at the Earth (Appleton & Barnett, 1925).

See publication for details:

Melin et al., (2025), Nat. Astro., doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-025-02507-9

Can XMM-Newton Be Used to Track Compositional Changes in the Solar Wind?

By Simona Nitti (University of Leicester)

Continuous monitoring of the solar wind ion composition is vital for understanding solar-terrestrial interactions, particularly through the study of Solar Wind Charge Exchange (SWCX) emission. SWCX produces soft X-rays (<2 keV) when highly charged solar wind ions (e.g., O7+, O8+, C6+) interact with neutral atoms. This emission is ubiquitous across the solar system, occurring wherever the solar wind encounters interstellar neutrals or interacts with planetary environments, including those of Earth, Mars, Venus, Jupiter, and Pluto.

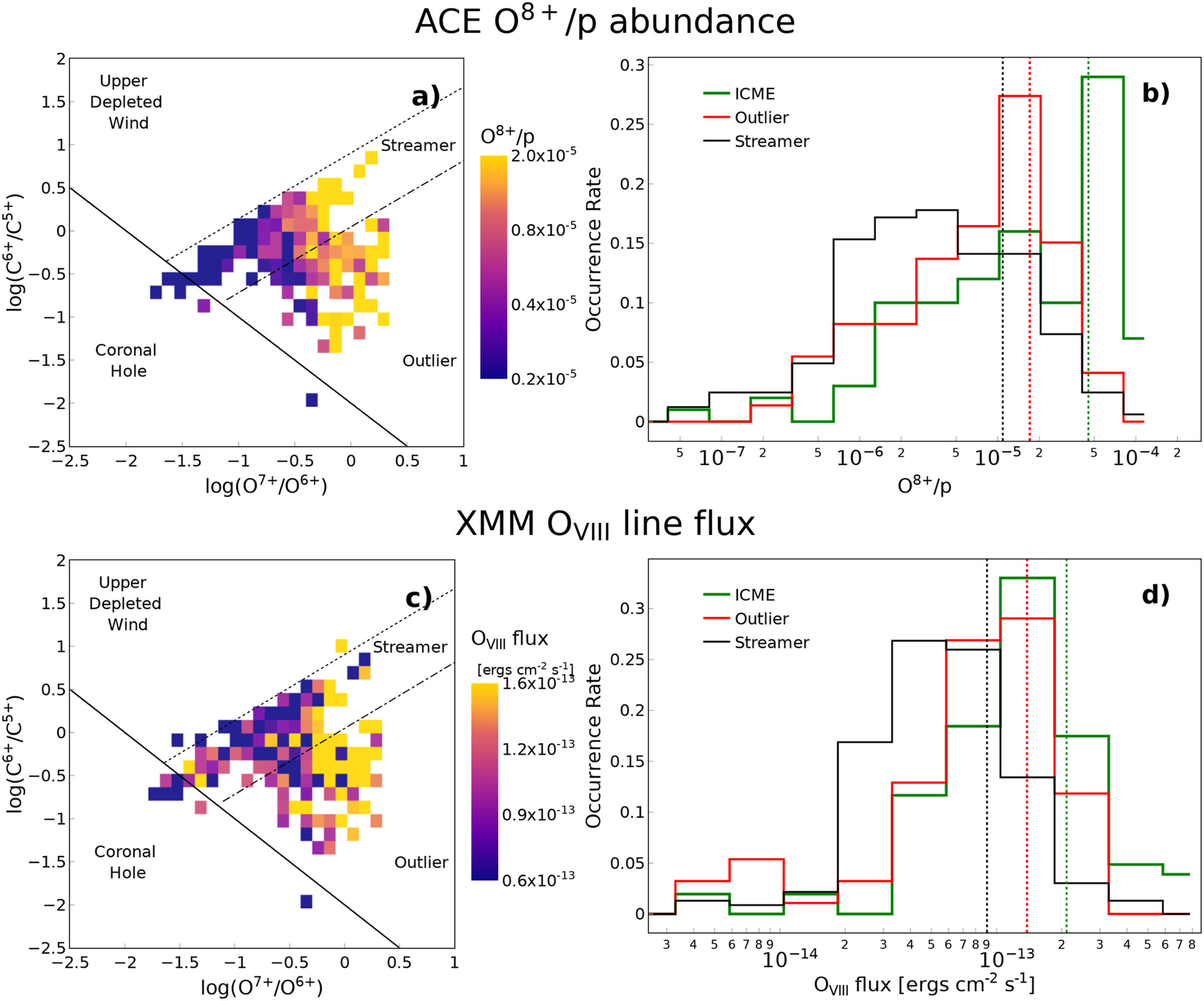

In this study (https://doi.org/10.1029/2024JA033323), we investigated whether SWCX emission from Earth’s exosphere, observed by the XMM-Newton telescope, can be used to infer solar wind composition. By comparing spectral line intensities extracted from XMM data with ion abundance measurements from the ACE spacecraft at L1, we found that OVIII emission closely tracks O8+ abundances. In contrast, other ions involved in the SWCX process—such as O7+, C6+, C5+, and Mg11+—do not exhibit a consistent correlation between their abundance and X-ray emission.

To explore whether XMM data still encodes information about the solar wind state, we employed a Random Forest Classifier to predict solar wind types, following the classification scheme by Koutroumpa (2024). Incorporating XMM features alongside proton parameters significantly improved model performance, with a macro-averaged F1 score of 0.80 ± 0.06, compared to 0.55 when using proton data alone. Notably, XMM emission features ranked among the top five most important inputs. Moreover, XMM emission features ranked among the top five most important predictors. This suggests that, while individual ion abundances cannot currently be inferred directly from emission fluxes, XMM still provides valuable insight into the solar wind type, from which an average compositional profile may be inferred. This work is particularly timely given the degradation of the heavy ion spectrometer onboard the Advanced Composition Explorer (ACE), which has left the scientific community without reliable near-Earth ion composition measurements since 2011.

(a) SWCX periods ACE O8+/p (where p is proton density) 2D histograms, averaged over their occurrence between 2000 and 2009, in a (O7+/O6+)×(C6+/C5+) space, with black lines separating different solar wind types.

(a) SWCX periods ACE O8+/p (where p is proton density) 2D histograms, averaged over their occurrence between 2000 and 2009, in a (O7+/O6+)×(C6+/C5+) space, with black lines separating different solar wind types.

(b). Occurrence rate of ACE O8+/p for the Streamer (black), Outlier (red) wind and ICMEs (green).

(c) (d) Same as left plots but for OVIII ion line fluxes from the XMM SWCX data set.

See publication for details:

, , , , , , & (2024). Can XMM-Newton be used to track compositional changes in the solar wind? Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, 129, e2024JA033323. https://doi.org/10.1029/2024JA033323