MIST

Magnetosphere, Ionosphere and Solar-Terrestrial

Nuggets of MIST science, summarising recent papers from the UK MIST community in a bitesize format.

If you would like to submit a nugget, please fill in the following form: https://forms.gle/Pn3mL73kHLn4VEZ66 and we will arrange a slot for you in the schedule. Nuggets should be 100–300 words long and include a figure/animation. Please get in touch!

If you have any issues with the form, please contact This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Nudging solar wind forecasts back towards reality

By Mathew J. Owens, University of Reading, UK.

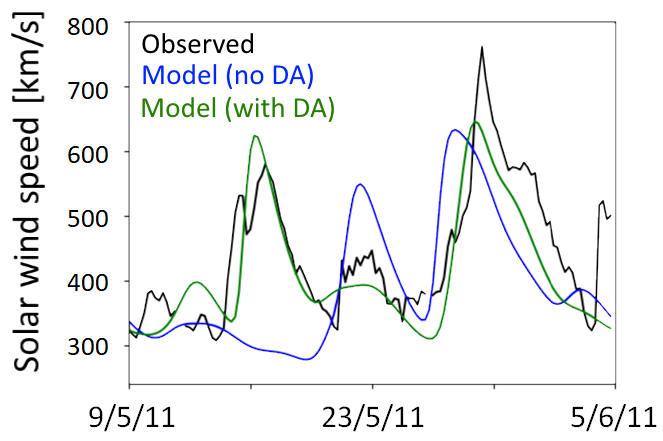

In order to forecast space weather, it is necessary to accurately model the solar wind, the continually expanding solar atmosphere which fills the solar system. At present, telescopic observations of the Sun's surface are used to provide the starting conditions for computer simulations of the solar wind, which then propagate conditions all the way from the Sun to Earth. But spacecraft also make direct measurements of the solar wind, which provide useful additional information that is not presently used. In this study we use a simple solar wind model to develop a method to routinely "assimilate" spacecraft observations into the model and thus improve space‐weather forecasts. This data assimilation (DA) approach closely follows that of terrestrial weather prediction, where DA has led to increasingly accurate forecasts. We use artificial and real spacecraft observations to test the new solar wind DA method and show that the error in predicting the near‐Earth solar wind can be reduced by around a fifth using available observations.

For more information, please see the paper below:

Lang, M.S., and M.J Owens. (2018), A variational approach to Data Assimilation in the SolarWind, Space Weather, 16. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018SW001857

Figure: Model near-Earth solar wind speed before (blue) and after (green) assimilation of STEREO in situ observations. The DA enables the model to capture a previously missed fast stream, corrects a false alarm and improves the timing of a third stream

School students discover sounds caused by solar storms

By Martin Archer, School of Physics and Astronomy, Queen Mary University of London, UK.

Earth’s magnetic shield is rife with a symphony of ultra-low frequency analogues to sound waves. These waves transfer energy from outside this shield to regions inside it and therefore play a key role in space weather - how space poses a risk to our everyday lives by affecting power grids, GPS, passenger airlines, mobile telephones etc.

While these waves are too low pitch for us to hear them, Archer et al. [2018] show that we can make our satellite recordings of them audible by dramatically speeding up their playback. These audio versions of the data can be used by school students to contribute to research, by having them explore the data through the act of listening and performing analysis using audio software.

An example of this is presented where school students from Eltham Hill School in London identified “whistling” sounds whose pitch decreased over the course of several days. This event started when a coronal mass ejection, or solar storm, arrived at Earth causing a big disturbance to the space environment. It turned out that the whistling sounds were vibrations of Earth’s magnetic field lines, a bit like the vibrations of a guitar string which form a well-defined note. While the solar storm stripped away much of the material present in Earth’s space environment, as it started to recover following the storm, this started to refill again. It was this refilling that caused the pitch of the sounds to drop slowly over time.

Previously events like these had barely been discussed and therefore were thought to be rare. However, many similar events were discovered in the audio which also followed similar disturbances, revealing that these types of waves are much more common than previously thought.

Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X6vbST9iMOU

For more information, please see the paper below:

Archer, M.O., M.D. Hartinger, R. Redmon, V. Angelopoulos, and B. Walsh. (2018), First results from sonification and exploratory citizen science of magnetospheric ULF waves: Long‐lasting decreasing‐frequency poloidal field line resonances following geomagnetic storms, Space Weather, 16, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018SW001988

Untangling the periodic ‘flapping’ and ‘breathing’ behaviour of Saturn’s equatorial magnetosphere

By Arianna Sorba, Department of Physics and Astronomy, University College London, UK.

At Saturn, the planet’s rotation axis and the dipole axis are aligned to within 0.01° [Dougherty et al., 2018], and so the magnetosphere’s magnetic field should be extremely azimuthally symmetric. However the Cassini space mission, which orbited Saturn from 2004-2017, observed mysterious periodic variations in the magnetic field at a period close to the planetary rotation rate. These observations suggested that the outer magnetosphere’s equatorial current sheet was `flapping’ above and below the rotational equator once per planetary rotation, to a first approximation acting like a rotating, tilted disc [Arridge et al., 2011].

However this ‘flapping’ picture does not fully explain the observed magnetic field periodicities. More recently, some studies have suggested the magnetosphere may also display ‘breathing’ behaviour; a periodic large-scale compression and expansion of the system, associated with a thickening and thinning of the current sheet [Ramer et al., 2016, Thomsen et al., 2017]. In Sorba et al. [2018], we investigate these two dynamic behaviours in tandem by combining a geometric model of a tilted and rippled current sheet, with a force-balance model of Saturn’s magnetodisc. We vary the magnetodisc model system size with longitude to simulate the breathing behaviour, and find that models that include this behaviour agree better with the observations than the flapping only models. This can be seen in the figure below, which shows that for an example Cassini orbit, both the amplitude and phase of the magnetic field variations are better characterised by the flapping and breathing model, especially for the meridional component (middle panel).

The underlying cause of this periodic dynamical behaviour is still an area of active research, but is thought to be due to two hemispheric magnetic field perturbations rotating at different rates. The study by Sorba et al. [2018] provides a basis for understanding the complex relationship between these perturbations and the observed current sheet dynamics.

For more information, please see the paper below:

Sorba, A.M., N. Achilleos, P. Guio, C.S. Arridge, N. Sergis, and M.K. Dougherty. (2018), The periodic flapping and breathing of Saturn's magnetodisk during equinox, J. Geophys. Res. Space Physics, 123. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JA025764

Figure: Radial (a), meridional (b), and azimuthal (c) components of the magnetic field measured by Cassini along Rev 120 Inbound. Magnetometer data shown in black, flapping only model shown in red, and flapping and breathing model shown in blue. Annotation labels underneath the time axis give the cylindrical radial distance of Cassini from the planet centre, and Saturn magnetic local time.

Energetic particle showers over Mars from Comet C/2013 A1 Siding-Spring

By Beatriz Sánchez-Cano, Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Leicester, UK.

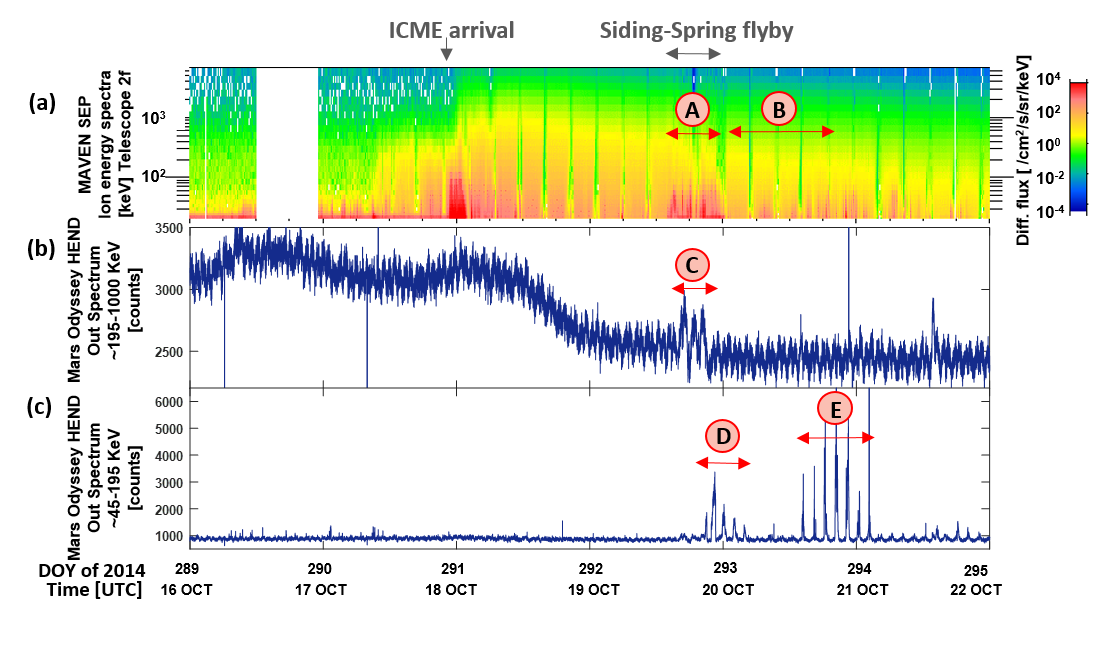

On the 19th October 2014, an Oort-cloud comet named Comet C/2013 A1 (Siding Spring) passed Mars at an altitude of 140,000 kilometres (only one third of the Earth-moon distance) during a single flyby through the inner solar system. This rare opportunity, where an event of this kind occurs only once every 100,000 years, prompted space agencies to coordinate multiple spacecraft to witness the largest meteor shower in modern history and allow us to observe the interaction of a comet’s coma with a planetary atmosphere. However, the event was somehow masked by the impact of a powerful Coronal Mass Ejection from the Sun that arrived at Mars 44 hours before the comet, creating very large disturbances in the Martian upper atmosphere and complicating the analysis of data.

Sánchez-Cano et al. [2018] present energetic particle datasets from the Mars Atmosphere and Volatile EvolutioN (MAVEN) and the Mars Odyssey missions to demonstrate how the Martian atmosphere reacted to such an unusual external event. Comets are believed to have strongly affected the evolution of planets in the past and this was a near unique opportunity to assess whether cometary energetic particles, in particular O+, constitute a notable energy input into Mars’ atmosphere. The study found several O+ detections while Mars was within the comet’s environment (at less than a million kilometers distance, see period A in the figure below). In addition, the study discusses several other very interesting showers of energetic particles that occurred after the comet’s closest approach, which are also indicated in the figure below. These detections seem to be related to comet dust tail impacts, which were previously unnoticed. This unexpected detections strongly resemble the tail observations that EPONA/Giotto made of comet 26P/Grigg-Skjellerup in 1992. In conclusion, the authors found that the comet produced a large shower of energetic particles into the Martian atmosphere, depositing a similar level of energy to that of a large space weather storm. This suggests that comets had a significant role on the evolution of the terrestrial planet’s atmospheres in the past.

For more detailed information, please go to the paper:

Sánchez – Cano, B., Witasse, O., Lester, M., Rahmati, A., Ambrosi, R., Lillis, R., et al (2018). Energetic Particle Showers over Mars from Comet C/2013 A1 Siding‐Spring. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, 123.https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JA025454

Figure: MAVEN and Mars Odyssey observations as a function of time of a powerful Coronal Mass Ejection on 17th October 2014, and of comet Siding-Spring flyby on 19th October 2014. It can be seen that from the point of view of energetic particles, the comet deposited a similar amount of energy than a solar storm on Mars’ atmosphere. (a) MAVEN-SEP ion energy spectra (b) Mars Odyssey-HEND energy profile from higher-energy channels. (c) Same as in (b) but for lower-energy channels. Periods A and B indicate the comet O+ detections at Mars. Period C shows similar detections although the particle identity cannot be determined. Finally, periods D and E shows dust tail impacts on the instrument.

The dependence of solar wind burst size on burst duration and its invariance across solar cycles 23 and 24

By Liz Tindale, CFSA, Department of Physics, University of Warwick, UK.

Time series of solar wind variables, such as the interplanetary magnetic field strength, are characteristically “bursty”: they take irregularly spaced excursions to values far higher than their average [Consolini et al., 1996; Hnat et al., 2002]. These bursts can be associated with a range of physical structures, from coronal mass ejections [Nieves-Chinchilla et al., 2018] and corotating interaction regions [Tsurutani et al., 2006] on large scales, down to small-scale transient structures [Viall et al., 2010] and turbulent fluctuations [Pagel and Balogh, 2002]. Over the course of the 11-year solar cycle, changing coronal activity causes the prevalence of these structures in the solar wind to vary [Behannon et al., 1989; Luhmann et al., 2002]. As energetic bursts in the solar wind are often the drivers of increased space weather activity [Gonzales et al., 1994], it is important to understand their characteristics and likelihood, as well as their variation over the solar cycle and between cycles with different peak activity levels.

Tindale et al. [2018] use data from NASA’s Wind satellite to study bursts in the time series of solar wind magnetic energy density, Poynting flux, proton density and proton temperature during 1-year intervals around the minima and maxima of solar cycles 23 and 24. For each variable, the duration of a burst and its integrated size are related via a power law; the scaling exponent of this power law is unique to each parameter, but importantly is invariant over the two solar cycles. However, the statistical distributions of burst sizes and durations do change over the solar cycle, with an increased likelihood of encountering a large burst at solar maximum. This indicates that while the likelihood of observing a burst of a given size varies with solar activity, its characteristic duration will remain the same. This result holds at all phases of the solar cycle and across a wide range of event sizes, thus providing a constraint on the possible sizes and durations of bursts that can exist in the solar wind.

For more information, please see the paper below:

Figure: Scatter plots of burst size, S, against burst duration, τD, for bursts in the time series of solar wind magnetic energy density, B2, extracted from one-year time series spanning i) the minimum of solar cycle 23, ii) the cycle 23 maximum, iii) the minimum of cycle 24, and iv) the cycle 24 maximum. The colours denote bursts extracted over increasingly high thresholds: the 75th, 85th and 95th percentiles of each B2 time series. The solid black line shows the regression of log10(S) onto log10(τD) for bursts over the 85th percentile threshold; the gradient of the regression for bursts over each threshold, alongside the 95% confidence interval, is denoted by α.